Writing about a film from fifty years ago is almost entirely pointless. There is nothing new I can say about

2001: A Space Odyssey. It might help that I'm not interested in saying anything new about it. I only want to write down some of thoughts I had while watching it, and that's probably what blogs are for. They didn't have blogs in 1968. As far as I know there was only advertising agencies and whisky. So this will have to do. I'm also not particularly interested in most of what there is to say about the film. I don't want to use the word 'masterpiece' and then pretend to be a film historian. I don't really care who Stanley Kubrick is. All I've got is what I saw when I watched the film for the first time. Here it is.

The Dawn of Man. Monkeys. I wonder how many film studies essays have been written about these monkeys. The arrival of a mysterious monolith shakes things up a bit.

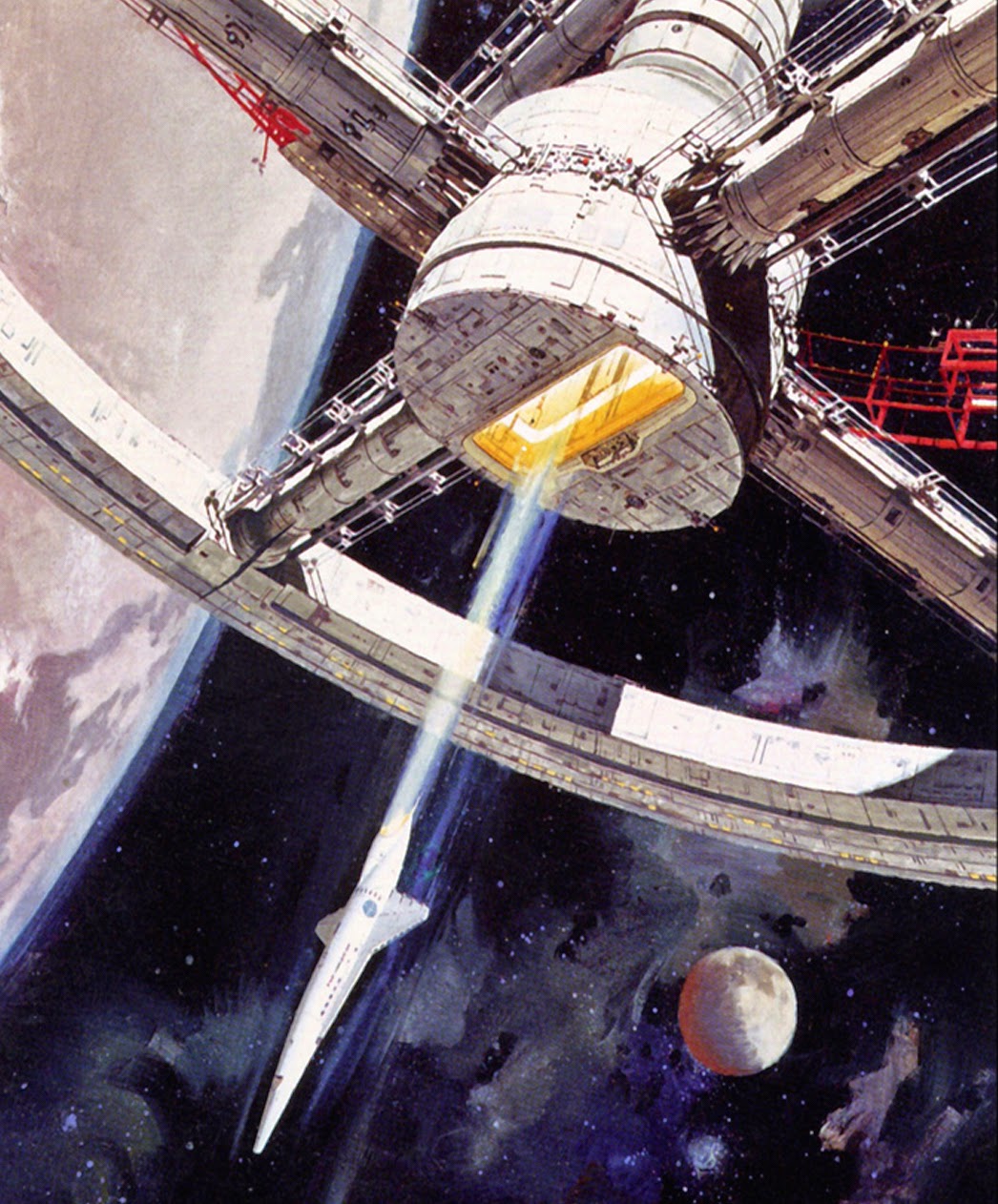

Spaceships, classical music. After skipping past pretty much everything, the film has slowed right down. Waltzing space stations, waltzing music. It's all very nice, but some of the interiors still look like a film studies class. I'm still imagining this essay: 'The juxtaposition of the red chairs in the foreground and the stark white walls of the background symbolise...' There's a time in school when you learn the word 'juxtaposition' and then attempt to use it in every essay. It's not something you would ever say out loud. It's an essay word. It's especially good to use in exams. Its real purpose is to say 'Look, I know the word "juxtaposition"'. That's at least five extra marks. You can go up a whole grade with 'juxtaposition'. Anyway, the people have found another monolith, and this one is a lot more interesting. Where did it come from? Who put it there? I think these are questions I'd be asking if this actually happened. After all, a mysterious monolith being buried on the moon isn't a lot more strange than the moon existing at all. It's all a big mystery, this universe. We don't know what it is, but we're here, and this lot are about to discover something new. It's the excellent droning soundtrack that's making me have these thoughts. Vast mysteries need vast music.

Bad robot. There's a while where this film is about a sinister machine, which is pretty much all I knew about it beforehand. It's definitely the most engaging 'film' part of the film. There's a plot, and dialogue, and it's clear what's happening. After the evolution of man, we've got the evolution of machines. No astronauts would actually have begun a voyage with a robot that has such a creepy voice. For such a complex machine, there must be customisation options. My Sat Nav has about a hundred accents and languages to choose from. They might have

chosen this voice. Of course, by this point the machine is doing whatever it wants, with all the cold logical certainty of an impassive red light that's decided it's better off without you. 'Don't shut me down, Dave. I'm afraid'. It knows how to code the humans.

Dave travels through the universe. It's time to question the universe again. Dave is going on a long trip through some lights, but these are some impressive lights. It's a rare space film that makes you feel like you're experiencing the vastness of space. That's not exactly possible, but the hypnotic, overwhelming, sensory overload of this part gives it a good go. When you read a book about space, or watch a documentary on physics, you have to stretch your mind out further than it's able to. I heard somewhere that the definition of fantasy is something that could never happen, and science fiction is something that probably will. But the truth is that there is nothing in any fantasy novel that is stranger than the actual universe we're in.

There are billions and billions of stars in the Milky Way - hundreds of billions - and our galaxy is just one of around a hundred and forty billion other galaxies, all with their own billions of stars.* This is all meaningless of course, because my brain can't comprehend how much a billion of anything is. There are vast millions of miles of nothingness in between all these balls of fire and planets and bits of rock and I don't know what else (black holes, I mean,

what?). The problem with thinking about all this is that you then have to readjust your mind back down to manageable distances, to the tiny bit of the universe you're in, where there's rugby and houses and films, and you're just generally meant to go about your business. Never mind though, because Dave is going to see what's at the other side of the universe, it's...

The end. What? I'm usually all for defusing grand themes with a joke, but don't take us through all that to show us... a strangely decorated bedroom, with towels. Up until now I thought the film was trying to show us something universal, but this is part of a specific sci-fi plot that I don't understand. All the tension is gone, and poor Dave grows old all of a sudden. Is this what would have happened to HAL if it had gone there by itself? I'd like to see the alternate ending where the robot works it all out, then looms over Earth with its big red light. Or at least just something else. I still feel disappointed by this ending. They showed us the universe then gave us a cardboard bedroom with underfloor lighting. Maybe this is what it'd be like if we did discover exactly what the universe was. All those scientists trying to figure it out are working towards a big anticlimax. Questions are more interesting than answers. What will we do when the big puzzle is solved? The collective response to the solving of the mystery of existence might be 'Okay then, what's next?'

Thanks Dave. Good film, though. Shame about the giant baby.

*A Short History of Nearly Everything, Bill Bryson